Core Training Explained

A good looking core is a goal that attracts many people to fitness, and it is a goal that is unlikely to go away any time soon.

A well developed core can also have significant contributions to many other aspects of your fitness.

Despite this, proper training of this part of the body has been made more confusing than any other.

So, the aim of this article is to dispel any myths you may have previously heard, and to give you the guidance that will actually move the needle for you.

This article’s table of contents include:

What the “core” actually is

Where common core training advice goes wrong

What a bad core exercise looks like

Good exercises for each part of the core

Guiding principles for your core training

My intention is for you to read this article once and have a full understanding of how to train your core and be fully effective in your efforts.

What muscles make up the core?

There isn’t any widely accepted definition to this term, and the range of muscles included in the term varies depending on your source.

For the purposes of this article, we’ll define it as the muscles responsible for moving your spine.

Broadly speaking, there are three groups of muscles that are responsible for this:

Abdominals

There are two muscle groups to discuss here:

Rectus abdominus

The vertical muscle in the middle

This is the muscle most people think of when they think of “abs”

Transverse abdominus

The triangle shaped muscle on the outer, lower part of the stomach

This is often referred to as the “corset muscle”

Both of these muscles can be found on the front of your abdomen.

For the purposes of training, the role these muscles play is to bend your spine forward or to resist your spine being bent backward.

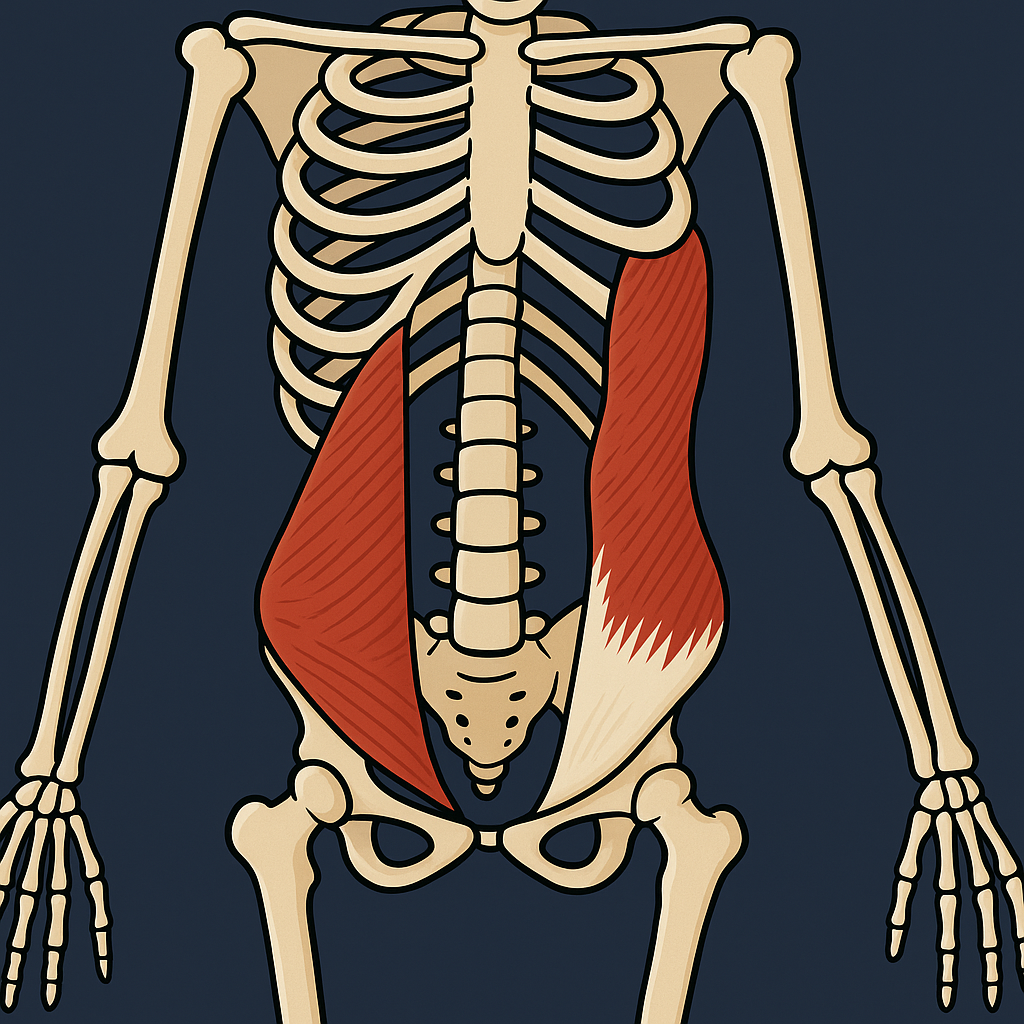

Obliques

These muscles can be found on the sides of your abdomen.

There are two to discuss here:

External obliques

These are the muscles on the right side of the image (on the skeleton’s left side)

Internal obliques

These are the muscles on the left side of the image (on the skeleton’s right side)

These muscles contribute to rotating your spine as well as bending your spine to the side.

Keep in mind, there are external & internal obliques on both sides of your body, I just used this image so that you could see both of them because they are layered on top of one another.

Paraspinal muscles

The term “paraspinal” just refers to being around the spine.

Here, there are numerous different muscles at play.

Going over each individual one wouldn’t be worth your time.

In general, their role is to bend your spine backward, or preventing it from bending forward.

And, again, these muscles would look symmetrical if I included the left and right sides of each muscle.

Where common core training advice goes wrong

Most of the core training advice you’ll see online is terribly misguided.

In my opinion, there are two reasons for this.

First, the muscles of the core, as we are defining it here, are responsible for moving the spine.

Second, the muscles of the core tend to be higher in type 1 muscle fibers.

I’ll break down each of these and explain how they misguide training, and what to focus on instead.

Myth 1: The role of the is to stabilize, not move, the spine.

Here’s the reality: in some situations your core muscles should work to stabilize your spine, but in other situations they should work to move your spine.

The idea that the job of the core is just to stabilize the spine and not to move it seems to come from two lines of reasoning.

Some activities in life do require your spine to be stabilized for your arms or legs to have proper coordination.

The misguided belief that moving your spine is dangerous.

Examples of a situation in which your spine must be kept still include driving and deadlifts.

If you’re turning your car right or left, then you’ve likely felt the muscles of your core contract while your rotate the wheel.

Similarly, during a deadlift, your legs can generally work more efficiently if your torso is held in the same position throughout the lift.

However, there are many scenarios where you must be able to move your spine, such as reaching for the backseat of your car from the driver’s seat.

All-in-all, there are over 70 joints along the spine contributing to movement. To keep them still forever would restrict many normal tasks throughout your day.

The idea that moving your spine, or training your spine through a range of motion, is dangerous is a myth that I covered in detail here:

Myth 2: The core should be trained with long durations since it has a high concentration of type 1 muscle fibers

Broadly speaking, muscle fibers can be classified into two camps:

Type 1 (slow twitch) muscle fibers which don’t produce force quickly but can last a long time (think endurance)

Type 2 (fast twitch) muscle fibers which can produce force very quickly but cannot last for a long time (think power & strength)

Muscles may be biased toward one or the other.

Certain muscles, called ‘postural’ muscles, tend to be biased toward type 1 muscle fibers.

These are called postural muscles because they are the muscles that work all day long to hold your body up. So, it makes sense they require the resistance to fatigue.

Examples include the calves and, you guessed it, the muscles of the core.

Many have been led to believe that muscles that are predominately comprised of type 1 muscle fibers should be trained with low weight and high reps or high durations.

In my opinion, this has birthed the trendy “ab circuit” videos that dominate Instagram.

However, this thought process implies a fundamental misunderstanding of how to structure training.

You shouldn’t train a muscle for what it already is, you should train it for the adaptation you want it to achieve.

If building muscle and strength is what you want for your core, then you should focus your training on the practices specific to these adaptations, not what the muscles default settings are.

The research overwhelmingly suggests that the fiber composition of a muscle does not impact what the best training practices for hypertrophy or strength. [1]

The most important part of this article

The bottom line is this: you should train your core the same way you would train any other muscle group.

The details of this will be discussed later.

Example of a bad core exercise

As I alluded to previously, core training recommendations tend to vary more than any other aspect of training. This is particularly true across social media.

The next section will cover exercises I commonly program for clients for proper core development. I thought it would also be helpful, though, to discuss what a truly unhelpful exercise core looks like.

Take the below example:

This sort of exercise does require the muscles of your core to stabilize so that you do not fall over.

However, there really isn’t much of a challenge being placed on them. The loading they would experience in this sort of exercise is unlikely to be sufficient to drive any meaningful adaptation.

The same would be true for overhead march variations, around-the-worlds with a kettlebell, etc.

To be clear: I am not saying this is a bad exercise overall. There are instances where this would be reasonably used in a program.

However, if core development is the goal, this exercise is unlikely to be of any real benefit.

Exercises (good ones) for each part of the core

In this section, I will provide you with exercises you can use to train each movement the core is responsible for: flexion, lateral flexion, rotation, and extension.

How to go about programming these throughout the week will be discussed in the next section.

Core activation during compound lifts

You are probably already of the understanding that most compound lifts require significant core activation.

This includes exercises such as squats, deadlifts, bent over rows, standing shoulder press, etc.

In fact, the demands placed upon your core are some of the primary reasons you would elect to perform such exercises.

In contrast to the “bad” example we just discussed, these sorts of movements will place a sufficiently challenging stimulus to the core to elicit a meaningful adaptation.

This will not occur to ALL of the muscles of the core, however.

The core activation during these sorts of movements will be primarily limited to the paraspinal muscles as well as the transverse abdominus.

Since these kinds of movements are included in most good programs, direct training to these muscles is rarely something that is needed.

We’ll discuss this more in the programming section of this article.

Flexion: abdominal training

The three most common movements I program under this category are as follows:

Cable crunches

Hanging leg raises

Normal crunches

planks

Cable crunches are my #1 on this list as they allow you to load the abdominals most easily and most directly.

The key to this movement is staying still at your hips and arms and letting all movement occur around your spine.

If the technique is difficult to get down, then performing a few sets of cat cows beforehand can help.

The hanging leg raise is an exercise that I like because it places a high load on your abs, hip flexors, grip strength, while also providing a good stretch to the lats.

Now, while these can certainly be effective for developing the abdominal musculature, there is a lot more going on than in the cable crunches. This may distract from the quality of contraction you can deliver to the abs specifically.

That said, if you don’t have access to a cable machine and your grip is strong enough to sustain these, they may be your best bet for ab development.

Planks may be the most popular “core” or “ab” exercise of all time.

In some circles, they get a lot of hate because they are an isometric- meaning it’s a position you hold and does not have a range of motion.

However, I believe the plank may be an underrated exercise for a couple reasons.

First, it requires notable activation of the serratus anterior. This muscle is part of your shoulder complex.

Its main function is protrusion of the shoulder; think pushing your shoulder blades forward, as if you were reaching forward for something that is just out of reach.

This muscle is required for normal, strong function in most pressing movements. This, building strength in this muscle can oftentimes make bench pressing and shoulder pressing feel better.

Second, it requires notable activation of the hip flexors, particularly the rectus femoris (because the knee is extended) and the iliopsoas.

Similar to the serratus anterior, developing these muscles is important for normal hip and knee function.

With all of that said, these muscles are not so important that they need their own exercise slot in a workout. Your time is limited, and the stimulation they get from an exercise such as a plank is likely to be enough to derive whatever benefits there may be for you.

Lateral flexion: oblique training

The two most common lateral flexion exercises I program for clients are:

Side bends

Side planks

The side bends are likely to be the better movement for the obliques specifically as they take them through a fuller range of motion.

However, the side planks can be a nice movement to incorporate intermittently as they will also require notable recruitment of the hip abductors and adductors; which may mean you don’t need to train them elsewhere.

All-in-all, the better choice depends on what the program overall looks like.

Rotation: oblique training

For rotation, my go-to exercises are:

Cable torso rotations

Windshield wipers

The cable torso rotation is likely the best option here as the potential for loading and progression is much greater.

That said, the windshield wipers can be quite difficult when done right. So, they offer a good amount of room to progress as is.

Primarily, the difference here is whether or not the upper or lower body is majorly recruited as well.

If you structure your strength training into upper and lower body trainings and you want to incorporate rotational training, then it can become clear which is the better choice.

The kneeling torso rotation machine is likely the BEST option you are likely to find in regard to rotational training. However, I find it hit-or-miss whether or not a gym has this machine.

So, to make this article apply most broadly, they were exlcuded.

If your gym has one, though, use it.

Extension: paraspinal training

As we previously mentioned, your standard compound lifts will stimulate these muscles sufficiently.

So, I’m often reluctant to program direct training to these muscles.

However, there are times when such a movement is necessary and helpful.

When I do want to program direct training to the paraspinals, the two movements I most commonly use are:

Jefferson curls

Supermans

Think of Jefferson curls as being the opposite of an abdominal crunch.

If you feel as though the strength of your lower back is the limiting factor for your main lifts, this movement can be extremely helpful.

It can also be useful to build tolerance in your lower back. For instance, if you build up strength on this exercise, it isn’t unreasonable to say that your likelihood of “throwing your back out” in day to day life decreases.

Similar to my commentary on planks, I believe supermans to be a rather underrated exercise.

They are included in this article because of their stimulus to the lower back, but they do much more than this as well.

For instance, take note of the position of my arms. They are overhead and elevated against gravity.

This serves to increase to load on the back muscles. However, it also is primarily driven by another important shoulder complex muscle: the lower trapezius.

Similar to the serratus anterior, this muscle is important for normal functioning in your pressing movements. Developing strength in this muscle can oftentimes make your pressing feel better.

Programming core training

The principles behind programming training your core are not dissimilar to programming for other muscles; but there are a few key things to keep in mind.

Regarding volume, my recommendation is ~4-12 sets per muscle group per week; same as any other muscle group.

Regarding intensity, my recommendation is to take each set ~2-3 reps shy of failure, or at least display a high level of effort if using an isometric exercise (plank, side plank, superman). Again, not too different from other exercises.

Finally, in regard to frequency, I recommend splitting your weekly training volume into 2-3 sessions per week; but this is unlikely to be too significant of a consideration.

In other words, if you are going to perform 10 sets for a muscle group in a week, it is unlikely to make a huge difference in your results whether that volume is split up into 1, 2, or 3 sessions. [2]

The main thing to keep in mind is that your abdominals and obliques work together on many movements.

For instance, when you perform a crunch, the obliques on each side contract to help your abdominals in the movement.

So, if you are training abs in a given session, you probably do not need to add an oblique exercise on top of this and vice versa.

Crunches certainly aren’t as direct of an exercise for the obliques as rotations or side bends are, but they are good enough to not absolutely necessitate the extra training time if it isn’t a huge priority for you.

So, I would give err on the side of lower direct volume for your abdominals and obliques because of this.

In regard to paraspinal muscle training, most compound movements you perform will contribute to your total training volume. This is also true for the transverse abdominus.

Squats, bent over rows, deadlifts, and all similar exercises will all count.

It is likely that you will not need to add more paraspinal training on top of this.

As we mentioned before, the primary indication for doing so would be if the strength of your lower back is the limiting factor on a given main lift, such as a squat or deadlift.

Final notes

There’s a lot of creativity that had to be left out of this article for the sake of keeping it concise.

An example would be all regressions and progressions (apart from changes in weight) on each exercise.

Point is: don’t let the exercise and programming guidelines here box you in. They will work great, of course, but understand that the optimal programming structure for you may require stepping outside of the box a bit.

If nothing else, the primary take-home I’d want you to have from this article is the following:

Your core should be trained like any other muscle. The same way you’d train your quadriceps, glutes, chest, or biceps is how you should train your core.